The Uptime Imperative

Posted October 23, 2025

Chris Campbell

Countries don’t buy Patriot missiles because they’re profitable. They buy them because they’re cheaper than getting blown up.

Sure, the thing it shoots down might be a $10,000 rocket—but that rocket might be aimed at a city.

Put a different way…

Nations don’t invest in defense for return on capital. They do it for return on existence.

In business, the same logic is increasingly crucial for uptime.

AI clusters, telecom backbones, energy grids—all depend on continuous service.

In the internet age, decentralization is the long-term solution.

BUT it’s true: decentralization is (usually) more expensive than its centralized counterpart.

A centralized grid can deliver electricity for ~$0.10–$0.15 per kWh. Meanwhile, remote microgrids (solar + battery + diesel backup) often cost 2–4× more per kWh.

So why is there such an extreme investment in microgrids? Because, increasingly, institutions are willing to pay the premium for energy sovereignty and uptime.

Consider also Starlink.

Starlink’s constellation cost more than US $10 billion to deploy. Each user terminal costs more than $500 (vs. $50 fiber installation).

So why do we need Starlink? Because it provides internet to ships, disaster zones, and war zones—places fiber never reaches. In Ukraine, when terrestrial networks went dark, Starlink terminals restored battlefield command and hospital comms within hours.

Now back to Patriot missiles.

Each Patriot missile battery (~US $1 billion) defends a single metro region. Duplicated command networks multiply cost.

So why has the US spent almost $100 billion on these systems? Because militaries pay exponential premiums for redundancy: two satellites instead of one, dispersed command centers instead of centralized HQs.

The U.S. nuclear triad (air, land, sea) is 3× redundancy by design. The cost of redundancy is the cost of deterrence.

The reason most things don’t work like this is simple…

Because for a long time, the economics weren’t there. But now they are. And that changes everything.

Downtime Was < Centralization

For most of modern history, downtime was cheaper than decentralization.

Factories could stop for a day, banks could close on weekends, and no one noticed when a network flickered offline.

Centralization is efficient. It minimizes waste, maximizes scale, and accepts the occasional outage as the price of progress. And the math worked: why build two of everything when one was good enough most of the time? After all, downtime in most cases was a rounding error.

But now, with the internet, that logic is beginning to invert.

Today, every system—financial, digital, industrial—is wired into everything else.

A hiccup in one region becomes a seizure across the network. When AWS or Visa or the Texas grid goes down, the losses are increasingly catastrophic.

And not only on a whole. Individual costs are increasingly disastrous, too.

When Delta Air Lines went dark after a faulty CrowdStrike update, it canceled 7,000 flights and lost $500 million—all from a few lines of bad code.

In 2021, a single compromised VPN password shut down the Colonial Pipeline, choking 45% of East Coast fuel supply.

In 2019, Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq oil facility was crippled by a swarm of cheap drones, briefly cutting 5% of global oil production.

My point?

Downtime is beginning to cost more than decentralization.

A survey by IT IC found that 44% of enterprises report hourly downtime costs exceeding US $1 million, and 23% exceed $5 million per hour.

Another source (BigPanda) says unplanned downtime now averages ~$14,056 per minute, rising to $23,750/minute for large enterprises (which equals ~US $1.4 m–US $1.4 m+/hour) in 2022.

The global cyber insurance market (which covers many uptime risk vectors) is estimated at US $16.6 billion in premiums in 2024. Estimates suggest this will reach $75 billion by 2033, a 5x in less than a decade.

As more and more comes online, the uptime imperative grows exponentially. And that’s a pretty big opportunity for those who see where it’s heading.

The Uptime Imperative

Centralized, monolithic infrastructure is fragile in ways few appreciate. Many failures start in small cracks (software bug, cable deferred, single password) but cascade into big ones.

Therefore, building infrastructure defense through decentralization is a global imperative.

We’re already seeing it happen, but one of the most important and overlooked trends is a tiny sector called Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Networks… or DePIN.

DePIN turns physical infrastructure into open-source marketplaces: anyone can plug in a router, GPU, or solar panel and get paid in crypto for keeping it online. Tokens are the incentive that coordinate millions of small operators into one global network.

From the outside looking in, DePIN networks—whether compute, bandwidth, or energy—look like just another crypto science experiment.

Interesting, useful in edge cases, but ultimately inferior.

But that’s the view from comfort, not crisis. In the calm, newfangled tokenized infrastructure looks dumb. In the storm, it’s the only lighthouse on the shore still beaming.

The economics are simple: as the maintenance and insurance cost of centralization rises, the relative value of open, distributed resilience compounds. We’re still early, but as the internet and AI feed off each other, complexity is compounding faster than systems can adapt—pushing this shift into overdrive.

(And some of these DePIN projects are already far cheaper than their centralized counterparts. So there’s that, too.)

No, we’re not hurtling into a world where crypto runs your toaster and your Wi-Fi router.

DePIN adoption will seep in. Slowly first, then suddenly.

And in two main ways:

One, as a backup and load balancer: the same way Bitcoin miners now dynamically modulate power demand to stabilize grids.

But before that, as a scavenger of inefficiency, slipping into the gaps big players can’t or won’t close.

There’s clear precedent for this one too: stablecoins.

The New Rules of Money

Tether, the world’s largest stablecoin, went from zero to major financial-infrastructure player in about ten years.

It succeeded not because it was the most elegant or tightly audited. It wasn’t.

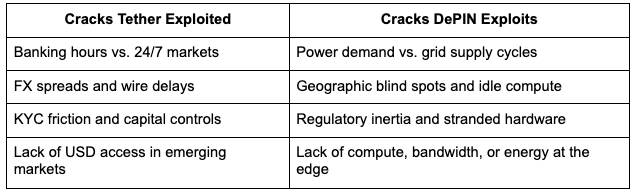

Its entire edge came from exploiting inefficiencies that centralized players can’t or won’t fix.

That idea sits at the center of my upcoming book, Tether: The Rogue Token and the New Rules of Money.

And it’s the same dynamic that will drive DePIN adoption.

Tether’s users didn’t care about ideology. They cared about uptime—the ability to move value now, without permission or delay.

DePIN users will be the same. And, increasingly, others will join because it’s cheaper to stay online than to go dark.

But it will start where the cracks are widest—rural energy deserts, edge connectivity zones, unmonetized GPUs, unlinked sensors—then seep into the core.

I’ll leave you with a line from John Seely Brown, who once led Xerox’s famed Palo Alto Research Center:

“The edge is where the action is—and where the future reveals itself first.”

The edge right now? DePIN.